Once you’ve brainstormed, gathered your research, and discovered your unique story, you can begin writing.

This week, I turned my attention to scriptwriting. Much like a film’s script, a comic’s script is a composite of dialogue and narrative description. As Piltcher and Gibbons argue, despite the fact that comics are typically characterized as a visual medium, the text must be considered of equal importance:

When writing for a comic that you will be drawing yourself, you might think, ‘I don’t really need to worry about the script–I’ll fix it in the art.’ But creating anything involves a number of steps, and if you miss one of these, you’re setting yourself up for trouble down the line. So even if I’m writing for myself, I still write a full script. I might not produce such extensive scene descriptions, but I’m just as careful with dialogue.

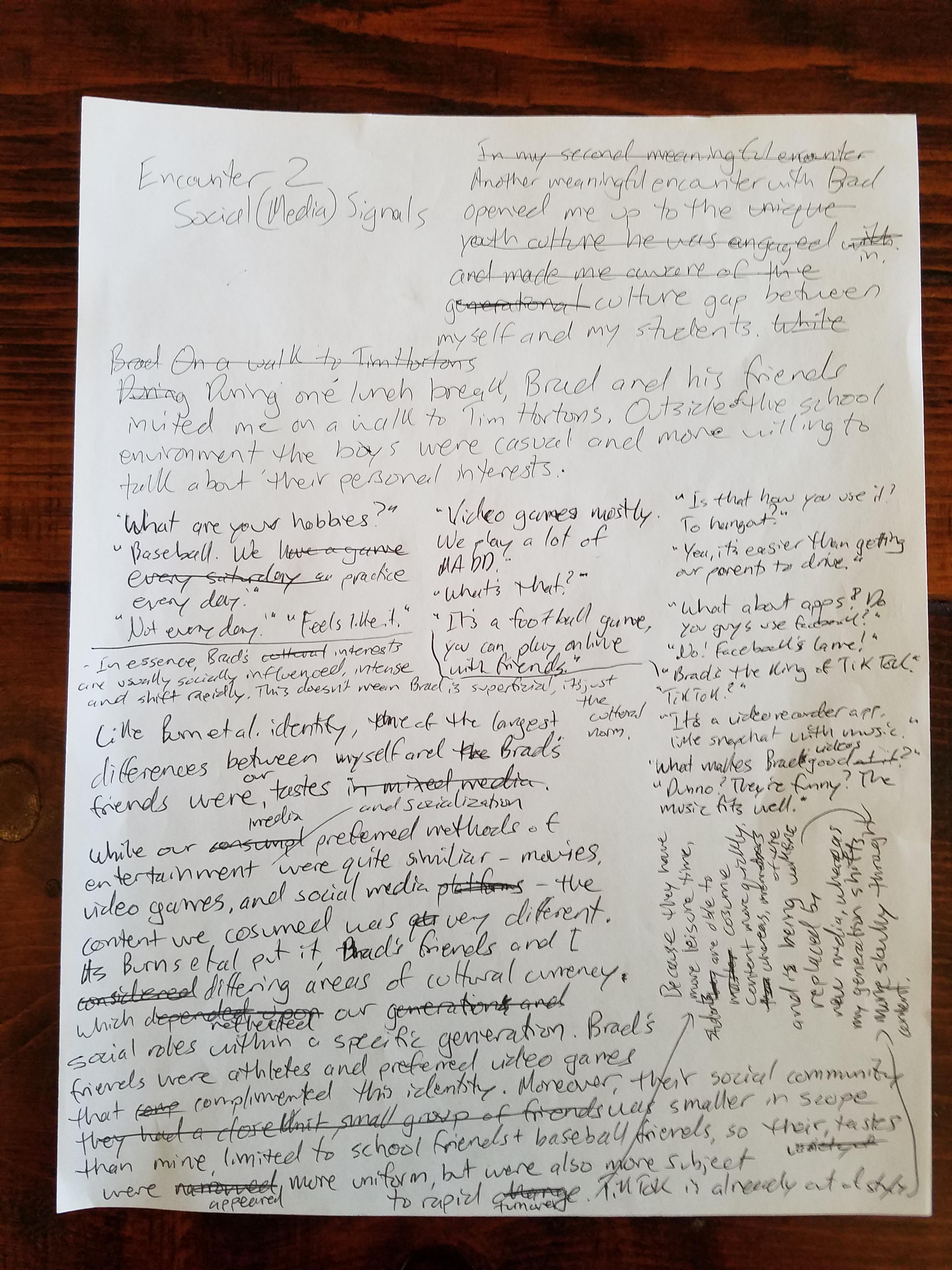

Illustrators at heart, Piltcher and Gibbons like to write their scripts with their graphics in mind, drawing out a very rudimentary storyboard, while developing dialogue and narrative exposition; however, they also note that many comic book writers, like Alan Moore, prefer to write strictly in the script or screenplay-type format and leave the graphic design to a partnering illustrator. Still, these authors must always consider the final product and write with the future graphics in mind. Moore, for instance, is notoriously known for writing meticulously detailed descriptions of what he pictures for each graphic panel. I chose to take Piltcher and Gibbons approach, hybridizing script and storyboard.

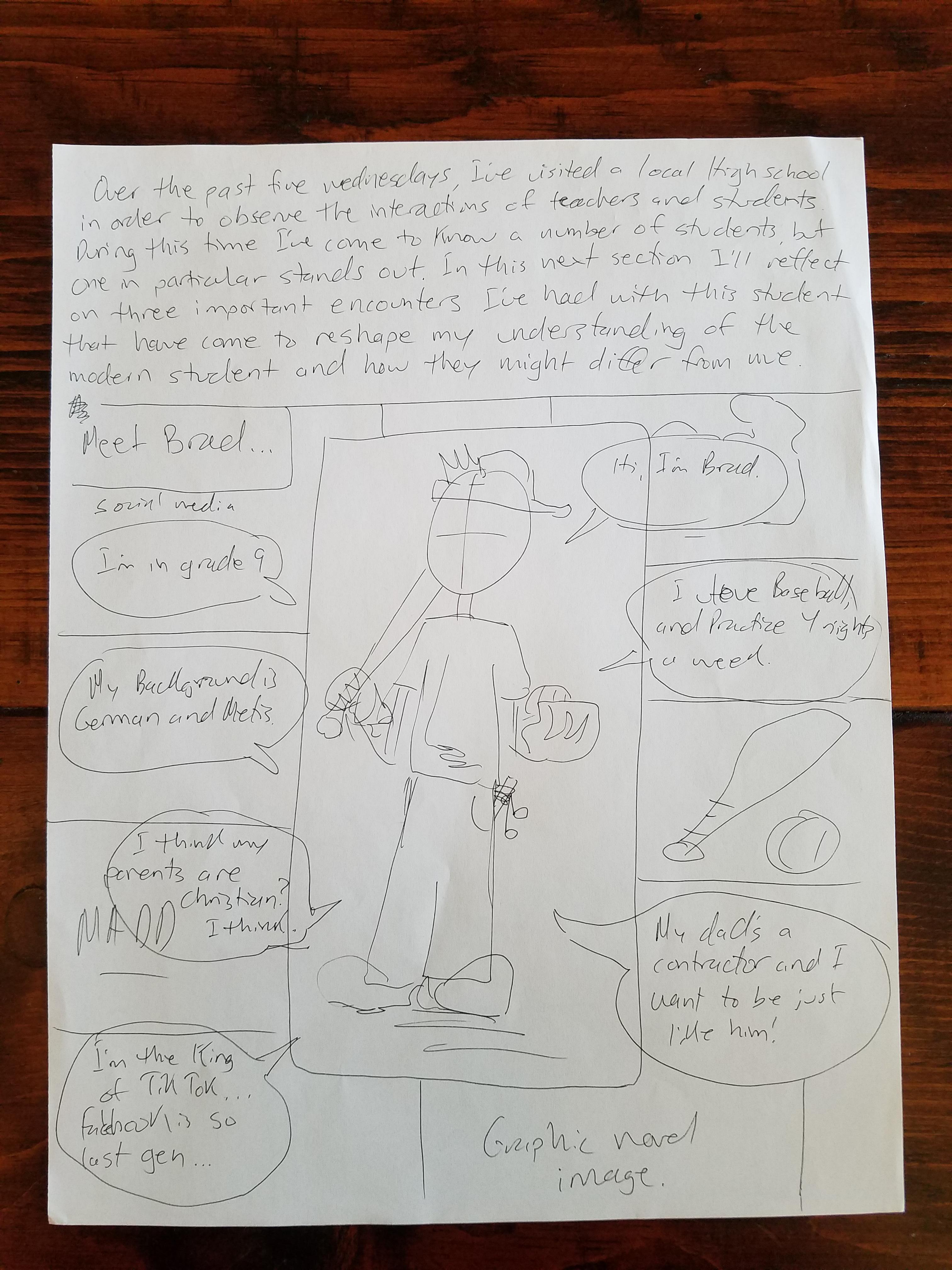

The final product looked something like this:

Some things I found particularly helpful about this process was the constant act of envisioning what each scene would look like. My script was heavily influenced by the graphics to come and, in turn, functioned as a helpful brainstorming session for the images to come. Furthermore, the act of writing things down in anticipation for the page prompted me to write succinctly and effectively. Only so many words can fit into a speech bubble, indeed, the skill of graphic novel writing is synonymous with conciseness, as Gibbons and Piltcher remind us,

A good story can always be told very briefly, so test yours by reducing each page down to a single paragraph. Break the whole story down page by page, treating each page as a unit of storytelling, and make sure you allow scenes to occupy whole pages rather than changing scenes mid-page.

Getting students to do this with their own research could help them isolate the most aspects. When you’re forced to reduce your argument or narrative down to three or four main points a page, you’re really forced to know the material inside and out. Here’s an example of my attempt at this planning stage:

My next step will be to tackle the visual groundwork of my comic, teasing out my particular illustrative style, hopefully, one that will be engaging but also manageable given my personal skill level. Additionally, next week I hope to find an easy-to-use comic book creator software platform to give this comic book a more professional feel.