“It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.”

–Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes.

The past few weeks, I’ve been gathering research for my comic from a variety of sources, including peer reviewed articles and my own interviews with local high school students. My studies have resulted in the discovery of some interesting insights regarding graphic media, pedagogy and bridging the cultural gaps between teachers and students.

A lot of the rhetoric these days tries to argue that because of digital media, students and teachers are more different than ever before (Burn et al. 88). However, there are others, like Andrew Burn, David Buckingham, Becky Parry and Mandy Powell, who see the situation differently. In their article “Minding the Gaps: Teachers Cultures and Student Cultures,” these researchers argue that the only real differences between students and teachers concerning digital media is the type of media they consume. As far as format or daily usage goes, teachers and students consume media in quite similar ways.

Still, Burn et al. acknowledge that there remain differences between Students and Teachers. Drawing from Bourdieu’s work on “cultural preferences,” they argue that “both groups represent particular dispositions, tastes and values related to their social roles,” meaning that the biggest difference between students and teachers are their social identities (90). So, how do we bridge the gap? Burn et al. suggest that Teachers encourage a “third Sphere” dynamic in their classrooms (88). That is, they seek to find areas of convergence between the curriculum and students’ interests, aspirations and worldviews. Thus, it’s especially important for me to learn about my students’ daily experience.

Over the past five Wednesdays, I’ve visited a local high school to become more comfortable with my future teaching environment. During this time, I’ve come into contact with a number of students; however, one in particular student (let’s call him ‘Brad’) stands out. I first met brad in English class where he already had a reputation for mischief. Brad’s funny and charismatic but not very interested in reading—largely because he’s dyslexic. When the teacher had the students pick a book for silent reading, Brad seemed hesitant. He eventually reached for a graphic novel. When I asked Brad why he chose a graphic novel over other texts, he shrugged and grumbled, “Cause, it’s not a real book.”

Graphic novels provide Brad with a form of narrative that don’t carry the same negative stigma as regular books, largely because they invite methods of reading that play to his strengths. I must recognize that not all my future students will share my linguistic ability or appreciation of written texts. For students like Brad, I’ll likely have to employ more creative multimedia strategies to break down those barriers against literature and classical texts. Once they’re down, I can guide students towards the kinds of literacies they’ll need to flourish in Post-Secondary education.

Why should teachers seek out the interests, beliefs and abilities of their students? Because all learning relies on previous experience! As the cognitive theorists Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky observe, students don’t simply compartmentalize new information and store it away. Rather learning is a dynamic process of taking existing knowledge and turning it into new knowledge or extending old knowledge to fit new circumstances. For this reason, it’s crucial that I attempt to draw from my students’ existing stores of knowledge, to ensure that they have sufficient building materials to construct new ways of thinking.

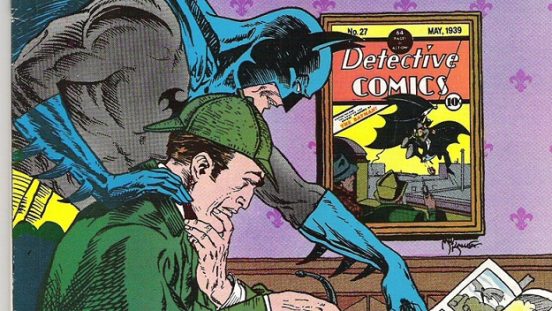

But what are some strategies for incorporating my students’ interests into the English classroom? Graphic novels offer a promising bridge for modern learners like Brad. While conventional novels communicate entirely through written text, graphic novels employ multiple types of literacy—including images, gestures, and lettering—and therefore invite interpretation from multiple angles. For students struggling with written literacy (like Brad) graphic images might be the bridge they need to improve their grammatical understanding. Moreover, the marriage of text and image better reflects the multimodality of many online platforms and, as such, better prepares students for interpreting the online textual landscapes of tomorrow.

For next week, I plan to take this research and channel it into a workable script, utilizing Gibbons and Piltcher’s script writing techniques outlined in their book How Comics Work.

Works Referenced

Booth, David and Kathleen Lundy. (2007). In Graphic Detail: Using Graphic Novels in the Classroom. Rubicon Publishing: Markham, Ontario.

Brenna, Beverly. (2013). How graphic novels support reading comprehension strategy development in children. Literacy UKLA, 47, 2, 88-94.

Burn, Andrew, David Buckingham, Becky Perry, and Mandy Powell. (2016). Minding the Gaps: Teachers cultures, student cultures. Adolescents online literacies, 39, 181-200.

McCloud, Scott. (1993). Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. Harper Perennial: NY, New York.

Piaget’s Theory of Constructivism. (2017). Teachnology.com, accessed, Oct. 15/19, http:// www.teach-nology.com/currenttrends/ constructivism/piaget/